In August 1969, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair took place on a dairy farm in Bethel, NY. Over half a million people came to a 600-acre farm to hear 32 acts (leading and emerging performers of the time) play over the course of four days (August 15–18).

In August 1969, the Woodstock Music & Art Fair took place on a dairy farm in Bethel, NY. Over half a million people came to a 600-acre farm to hear 32 acts (leading and emerging performers of the time) play over the course of four days (August 15–18).

Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, the Who, Janis Joplin and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young were among the line-up. Woodstock is known as one of the greatest happenings of all time and, perhaps, the most pivotal moment in music history and the history of American cultural politics. The Vietnam War was still raging. Thousands of young men were dying in the pursuit of a pointless war, fought against Ho Chi Minh, a former alley with the U.S. against the Japanese in WWII, whom we tried to depose as leader of North Vietnam.

Joni Mitchell said, “Woodstock was a spark of beauty where half-a-million kids saw that they were part of a greater organism.” According to Michael Lang, one of four young men who formed Woodstock Ventures to produce the festival, “That’s what means the most to me—the connection to one another felt by all of us who worked on the festival, all those who came to it, and the millions who couldn’t be there but were touched by it.” As to the greater organism, it seemed to be a product of the 60s, this kinship that we felt for one another, regardless of race, religion, or class.

By Wednesday, August 13, some 60,000 people had already arrived and set up camp. On Friday, the roads were so clogged with cars that performing artists had to arrive by helicopter. Though over 100,000 tickets were sold prior to the festival weekend, they became unnecessary as swarms of people descended on the concert grounds to take part in this historic and peaceful happening. Four days of music . . . half a million people . . . flooding rain, and the rest is history.

By Wednesday, August 13, some 60,000 people had already arrived and set up camp. On Friday, the roads were so clogged with cars that performing artists had to arrive by helicopter. Though over 100,000 tickets were sold prior to the festival weekend, they became unnecessary as swarms of people descended on the concert grounds to take part in this historic and peaceful happening. Four days of music . . . half a million people . . . flooding rain, and the rest is history.

Well, the farm is still there and the town, though enlarged with more restaurants, higher prices, more nostalgia/chatchke shops, foreign visitors, flashier cars than VW buses, as of Sunday and Monday, July 28 and 29, 2013, when my wife and I decided to escape from New York City for a breather, inhaling the past like a whiff of cannabis that brought back powerful memories, as we lounged about the pool of the Enchanted Inn Bed and Breakfast, where everyone, every conversation seemed smart and into something of social importance, from a less expensive retirement, preserving the environment to eating and living healthy. Not to mention a place where you could always hear poetry, read and applaud it, and hold some of the most beautiful views of the Catskill mountains and forests in your city-blurred eyes.

Of course, you still had your funky hippies with their Rasta braids walking Route 212 past some ramshackle crash-pads. But hey, it was Woodstock. Let it be. Billed as “An Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music” back in ‘69, the door was still open to wayfarers of all kinds.

During the sometimes rainy weekend, thirty-two acts performed outdoors in front of 400,000 concert-goers. It is widely regarded as a pivotal moment in popular music history. Rolling Stone listed it as one of the 50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock and Roll.

The event was captured in the 1970 documentary movie Woodstock, an accompanying soundtrack album, and Joni Mitchell‘s song “Woodstock“, which commemorated the event and became a major hit for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

The influx of attendees to the rural concert site in Bethel created a massive traffic jam. Fearing chaos as thousands began descending on the community, Bethel did not enforce its codes. Eventually, announcements on radio stations as far away as WNEW-FM in Manhattan and descriptions of the traffic jams on television news programs discouraged people from setting off to the festival.

Arlo Guthrie made an announcement, which was included in the film, saying that the New York State Thruway was closed. The director of the Woodstock Museum said this never occurred. To add to the problems and difficulty in dealing with the large crowds, recent rains had caused muddy roads and fields. The facilities were not equipped to provide sanitation or adequate first aid for the number of people attending; hundreds of thousands found themselves in a struggle against bad weather, food shortages, and poor sanitation, yet curiously liberated from the quotidian.

On the morning of Sunday, August 17, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller called festival organizer John Roberts and told him he was thinking of ordering 10,000 New York State National Guard troops to the festival. Roberts was successful in persuading Rockefeller not to do this. Sullivan County declared a state of emergency. During the festival, personnel from nearby Stewart Air Force Base assisted in helping to ensure order and airlift performers in and out of the concert venue. Ah, Nelson, trying to bring Vietnam back home again in the Rockefeller tradition again. I guess it wasn’t enough that you unleashed your commandos to put down the riot at the Attica Correctional Facility, killing 29 prisoners and 10 hostages, and injuring many more in the process.

Jimi Hendrix was the last act to perform at the festival. Because of the rain delays that Sunday, when Hendrix finally took the stage it was 8:30 am Monday morning. The audience which had peaked at an estimated 400,000 people during the festival was now reduced to about 30,000 by that point; many of whom merely waited to catch a glimpse of Hendrix before leaving during his show.

Hendrix and his band performed a two-hour set. His psychedelic rendition of the U.S. national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner” occurred about 3/4 into their set (after which he morphed into “Purple Haze”). The song would become “part of the sixties Zeitgeist” as it was captured forever in the Woodstock film; Hendrix’s image performing this number wearing a blue-beaded white leather jacket with fringe and a red head scarf, has since been regarded as a defining moment of the 1960s.

Although the festival was remarkably peaceful given the number of people and the conditions involved, there were two recorded fatalities: one from what was believed to be a heroin overdose and another caused in an accident when a tractor ran over an attendee sleeping in a nearby hayfield. There also were two births recorded at the event (one in a car caught in traffic and another in a hospital after an airlift by helicopter) and four miscarriages. Oral testimony in the film supports the overdose and run-over deaths and at least one birth, along with many logistical headaches.

Nevertheless, in tune with the idealistic hopes of the 1960s, Woodstock satisfied most attendees and then some. There was a sense of social harmony, which, with the quality of music, and the overwhelming mass of people, many sporting bohemian dress, behavior, attitudes and, let’s face it, drugs, helped to make it one of the enduring events of the psychedelic decade.

It taught young men like me, still in their 20s, to “just say no” to war and killing. Its rock and roll, its sexual revolution freed up waves of energy into the mainstream that last tol this day.

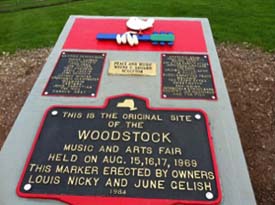

Economically speaking, in the middle of the town today stands a metal sign that stops people in their tracks in front of a one-time family market . . .

Economically speaking, in the middle of the town today stands a metal sign that stops people in their tracks in front of a one-time family market . . .

Sound for the concert was provided by sound engineer Bill Hanley. “It worked very well,” he says of the event. “I built special speaker columns on the hills and had 16 loudspeaker arrays in a square platform going up to the hill on 70-foot [21 meter] towers. We set it up for 150,000 to 200,000 people. Of course, 500,000 showed up.” ALTEC designed 4×15″ marine ply cabinets that weighed in at half a ton each and stood 6 feet (1.8 m) tall, almost 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, and 3 feet (0.91 m) wide.

Each of these enclosures carried four 15-inch (380 mm) JBL D140 loudspeakers. The tweeters consisted of 4×2-Cell & 2×10-Cell Altec Horns. Behind the stage were three transformers providing 2,000 amperes of current to power the amplification setup. For many years this system was collectively referred to as the Woodstock Bins. This wasn’t your father’s car radio for sure. But the collective “We” could use it to send out a whole new message, as did the baby-boomers of the late 60’s.

Though we were in Woodstock for just about 24 hours and had a delicious dinner in Big Bear restaurant in Bears Town, watching, from a window, a mountain stream with rain splashing in it . . . this time it was conversations about fracking that were going on. And we asked ourselves and our new friends back at the Enchanted Inn Bed and Breakfast, how we could ever do this to Mother Nature, pollute the water and land and beautiful green forests, destroy land and mountains for the filthy lucre made on natural gas, using fracking drills to pound and rip apart rock and earth, pouring their cocktail of toxic chemicals in, which eventually would ruin the land, the drinking water, the sky and plant life. Perhaps it was time for a new Woodstock. Perhaps it was long overdue.

If New York State had turned into a cause for massive protest, America, too, had now become an international force of destruction around the world. Could massive protests address it in any meaningful way? Was Occupy Wall Street enough, as once youth’s music and culture was? Or would it, too, be met as it had been with paramilitary police forces that were hell-bent on eliminating OWS.

I ask myself, where is the sense of joy we once possessed? Where is the Great Buddha, giver of ten thousand things, as Lao Tzu described, to hear our collective cry, and give us the wisdom to make our damaged world whole again? After all, I cleaned up my act to be a father of three, a working man, husband and grandpa over these past four decades. We could still be one people. But where did the love go? And when would what came around once, come around again? Peace.

Jerry Mazza is a freelance writer and life-long resident of New York City. An EBook version of his book of poems “State Of Shock,” on 9/11 and its after effects is now available at Amazon.com and Barnesandnoble.com. He has also written hundreds of articles on politics and government as Associate Editor of Intrepid Report (formerly Online Journal). Reach him at gvmaz@verizon.net.

How wonderful it was to be young in the sixties, an age of unbounded optimism fueled by antibiotics, birth control, general affluence, plentiful work, rising wages, free public higher education and an all-powerful dollar that made foreign travel cheaper than staying at home. There was a universal perception that things could only get better and better. It was great while it lasted.

Re: Tony Vodvarka: Ah, Tony, you remember it all. But don’t forget Vietnam, LBJ, Dickson, the lingering memory of JFK, and too many who sailed over the edge on Acid. But, yes, at least we felt free, to protest, to love, to have the Pentagon Papers and Daniel Ellsberg (representing a different New York Times). It published the truth, like Intrepid Report, no lies, no regrets, no b.s. Anyhow, as we used to say, “What goes around comes around.” And any one of these god-awful days in which we’re now living, days of surveillance and death penalties for whistleblowers, people will be patting more and more of those who tell the truth as heroes not “traitors.” The real traitors are the ones behind the NSA and its minions. Anyhow, good to hear from you. Stay loose, limit your TV watching, have at least one tie-dyed shirt in your wardrobe. And some rolling papers.

You never know,

Jerry Mazza